As an Executive Coach, the ability to focus is perhaps the single biggest struggle that I see clients facing. With incessant demands on our time and attention, endless collaborative opportunities, distributed work environments, and dependency on multiple communication platforms, it has become increasingly difficult to simply focus and get things done.

But we must look beyond these external realities and ask ourselves: how does focus work and moreover, how do we get focus to work for us? In digging into these questions, I found very splintered views on what kinds of focus are useful and which are not.

This article argues a few key principles:

- That there are distinct styles of focus that exist on a continuum

- That each style of focus has value to tap and limitations to manage

- That a key to high performance is the ability to fluidly shift between these styles of focus

We know from everyday experience that there are different types of focus—some moments we are intensely focused and other moments, we are completed scattered. However, this auto-pilot behavior in which we aren’t normally aware of our attentional states often feels accidental or automatic. Knowing how to intentionally “turn on” and “turn off” these focus states is key to a broad range of performance outcome including increased productivity, creativity, recovery, and pleasure.

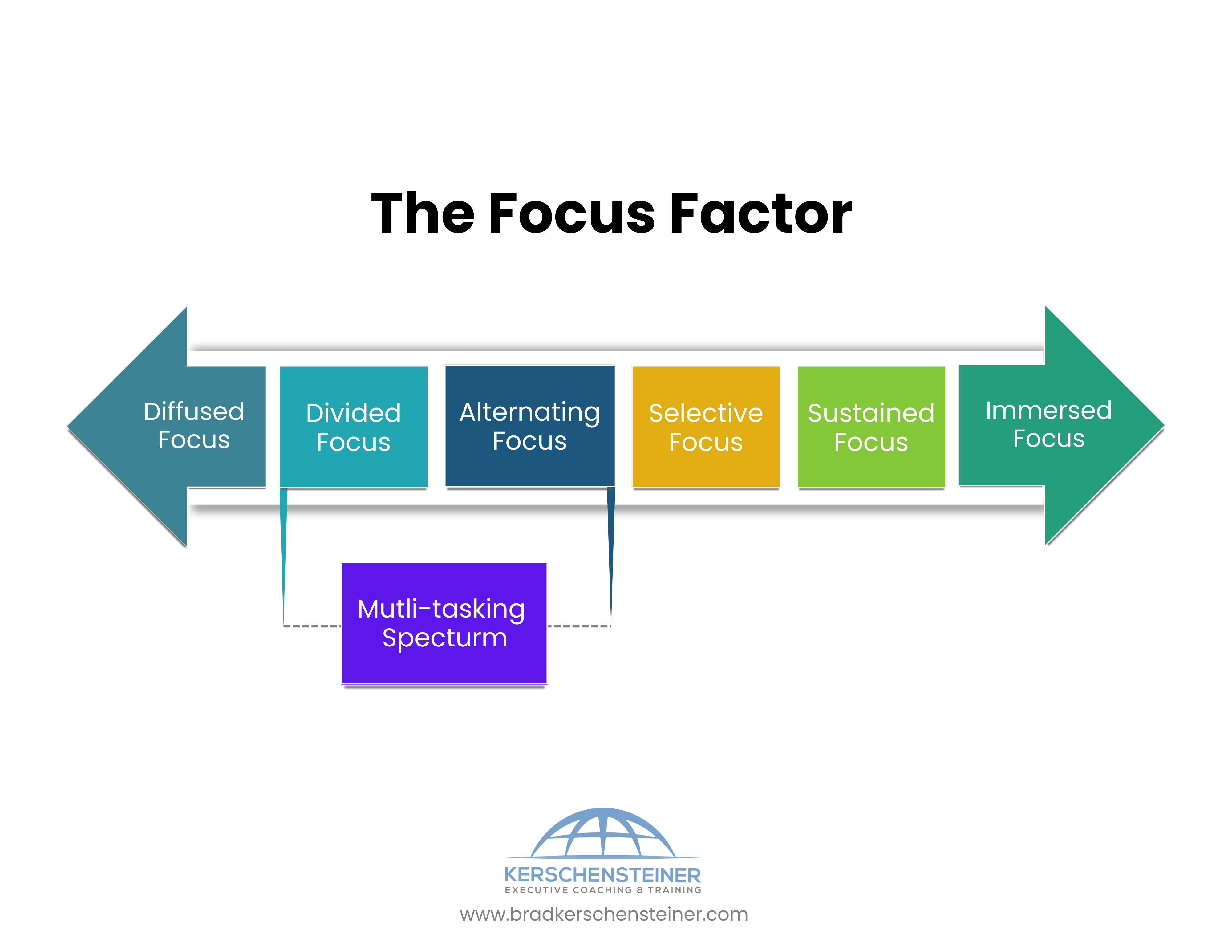

Below is a (working) model for the spectrum of focus styles. These are not hierarchal stages but states of focus in which specific attentional behaviors emerge. Immersive (or “flow”) Focus positioned at one end and Diffused Focus, at the other end. Although they are similar in some ways, they are subjectively very different experiences. In the middle of the spectrum you will find other attentional styles that comprise most of our daily experience—multi-tasking, selective and sustained focus. The goal is not to only to “achieve” Immersive Focus, rather to flexibly navigate these styles depending on what is effective for the situation.

Dimensions and Styles

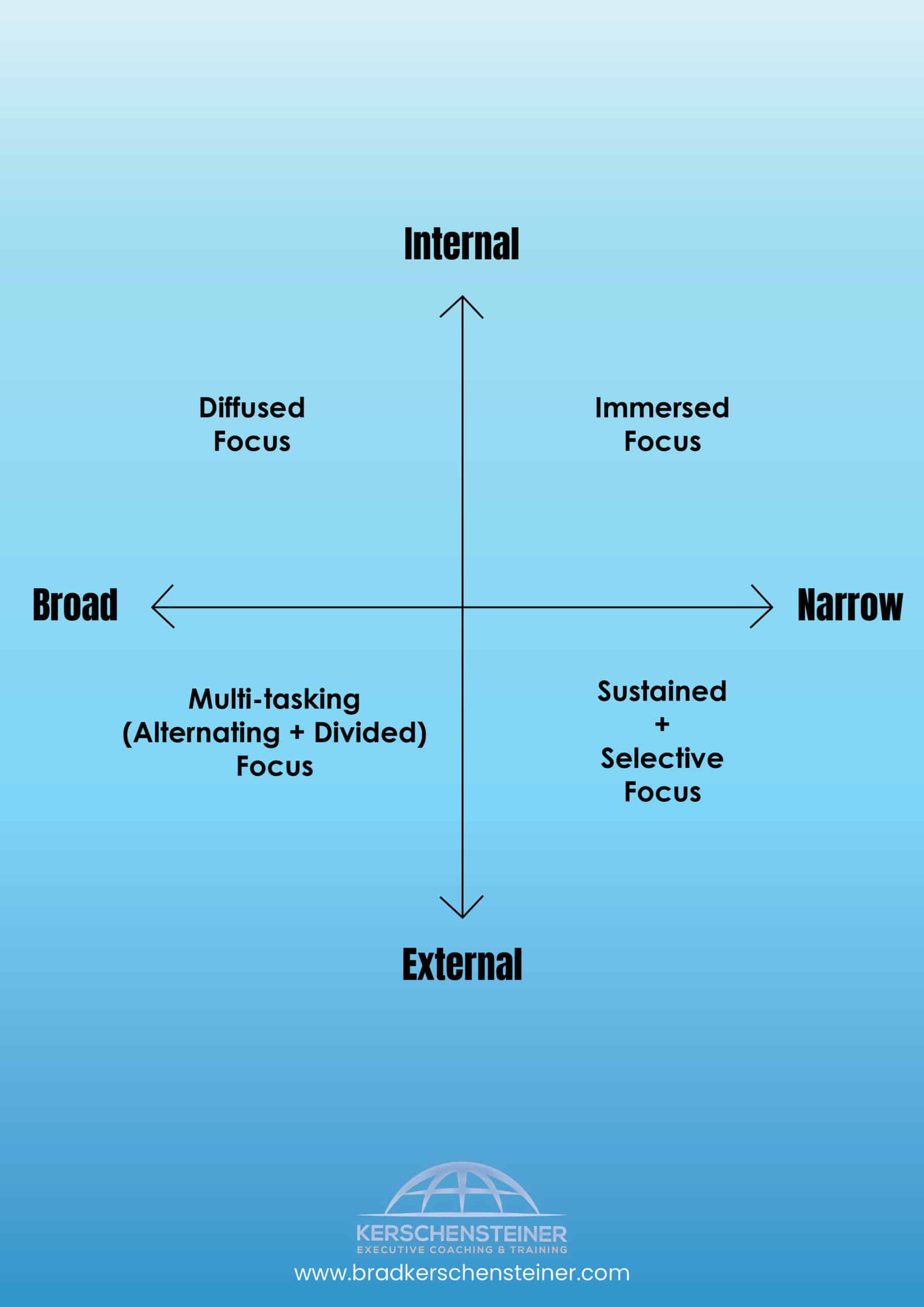

In the 1970s, Robert Nideffer developed the interesting Theory of Attentional and Personal Style in the field of sport psychology. In his studies on how high-performance athletes train, he found that they tend to fluidly shift between two dimensions: width (broad to narrow) and direction (external to internal) depending on the specific athletic challenge. A tennis player might mentally prepare in advance of the match (internal/narrow), be acutely aware of his movement in physical space on the court (external/broad), and analyze strategic options (internal/broad) to beat his opponent.

Nideffer found that across the various stages of athletic training and performance, athletes need to use all of these dimensions, yielding specific styles of attention (Focused/Systemic/Strategic/Aware).

In understanding work performance, Niedeffer’s four dimensions are useful although the specific styles are more applicable to studying athletic performance. Let’s re-work and overlay Nideffer’s attentional dimensions (broad/narrow; external/internal) with the common types of focus found in the workplace:

Ask yourself: what is your primary attentional style? What are the advantages and challenges to this? What other styles do you typically neglect or avoid?

Types of Focus

Immersed Focus

Immersive or “flow” states were studied by psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi and since popularized in the positive psychology movement. Flow refers to when you are completely absorbed in the performance of an activity.

In multiple research projects, the flow experience is subjectively described as energizing, highly focused, effortless, goal oriented, and feeling in control. In his seminal research, he found six characteristics of the flow experience. In flow, there is also typically a high level of concentration on a limited field in which one has experience.

In other words, it is difficult to have Immersed Focus in something we have limited experience or lack a disciplined practice. I am unlikely to get into a flow state in playing chess if I have only played a few times before. This absorbed task engagement involves an inhibition of task-irrelevant thoughts that we also see in Sustained Focus. Finally, in the research on Immersed Focus, individuals show low-levels of stress, worries and self-referential thinking. There is also significant research exploring the neuroscience of flow states, specifically the LC-NE system which regulates decisions regarding task engagement vs. disengagement.

Immersed focus doesn’t just happen although it can feel like it. In the research on flow, there are certain conditions that must be created:

- There must be a match between your skills and the challenges of a task. You are more likely to get into flow if you are engaging in a task that slightly challenges you. Over-load creates overwhelm and an underload leads to apathy.

- Having a clear goal in mind.

- The task must give you immediate and clear feedback.

Barriers to Flow & What You Can Do

Flow is often idealized as some sort of attentional end-state, implying other focus states are inferior. In my Coaching experience, Immersed Focus are incredibly uncommon for the everyday employee. Flow states are typically researched in “high-performers” like senior executives, athletes, etc and unfortunately there is an air of exclusivity to the literature on flow states and peak performance.

Aside from practical workplace barriers, some people do not enter flow states due to their personality style. In one critical study, flow proneness is actually associated with low levels of neuroticism and high levels of conscientiousness (traits found in the Big 5 personality assessment). So how do you enter flow if you tend to have these personality styles?

- First and foremost, know your personality style. Increase your awareness regarding any tendencies to over-index on traits like neuroticism (including self-doubt, having negative feelings, anxiety, etc.).

- Find ways to cultivate qualities that will make you more “flow-prone” (like openness, curiosity, persistence).

Finally, it appears that flow states can be addictive, making other focus styles seem unattractive or inferior. Individuals who are fixated on Immersed Focus likely need to access other attentional styles for more sustainable performance in the long-run.

Sustained Focus

Sustained focus involves vigilance of and concentration on a stimulus (i.e. a task or activity) for a long period of time. A central feature is the ability to determine what is relevant information and to block out irrelevant information. While sustained focus is necessary to accomplish many mundane activities at work, it also can be leveraged to complete work that requires complex problem-solving and strategic thinking. Sustained focus can be supported through simple strategies:

- Time-boxing your schedule

- Working in sprints

- Mono-tasking

- Eliminating all distractions for a set period of time

I position Sustained Focus and Immersed Focus in close proximity to each other on the focus spectrum above because experientially they are somewhat similar. However, there are a few key differences—flow is more of an alternated state while sustained attention is not. Also, in Sustained Focus you are not necessarily going to experience the “high” of flow states nor do you necessarily need to match your skill and challenge level; you simply need to block out unnecessary distractions so you can use focused problem solving in the service of accomplishing a task. Certainly a flow experience may happened during Sustained Focus but it is not necessary.

Most popular self-help/leadership development articles on time and attention management mistakenly only concentrate on this focus style. While yes we need to be able to withdraw from distractions and apply intense attention to things, we also need to be able to tolerate and work with distractions.

Selective Focus

Selective focus is the ability to attend to a specific stimulus in one’s environment and not on others . This style is externally focused, narrow (one specific task) and either visual or auditory. If you are leading a team meeting and hear a conversation in the hallway, you will (hopefully) block or “select out” this noise and focus on the meeting. While some visual and auditory stimuli be more distracting than others, this arousal state is very influenced by our perception of the stimulus.

Selective focus is incredibly important in today’s work environment because it allows us to prioritize in the moment what is important and filter out what is not. Here are some ways to improve your Selective Focus:

- Be aware of your perception of and reaction to visual and auditory stimuli. Depending on many factors, you may be more negatively aroused by certain environmental distractions. Know these triggers and keep them in check.

- Exercise improves improve selective attention by pre-activating your cognitive related neuronal networks.

- Pay deliberate attention to the task to improve its efficiency as well as your memory and recall.

Multi-Tasking Focus

Multi-tasking is seen as ineffective, unproductive, and less evolved than flow states of awareness in both the psychological and the self-help/leadership literature. The tendency to elevate flow states and demonize multi-tasking seems to feed into a larger misunderstanding of different attentional styles and how to use them adaptively.

By definition, multi-tasking is an attempt to do two or more tasks simultaneously and often involves switching back and forth between tasks (“context switching”). According to a 2004 study, knowledge workers switch tasks an astonishing average of 20 times per hour. Multi-tasking is typically broad in focus (a range of external cues and events) and external. Multi-tasking actually involves a spectrum of attentional styles and behaviors, including sequential and concurrent types.

When multi-tasking, our brain activates cognitive resources to meet those increased demands for attention and working memory. Multi-tasking can lead to reduced performance and efficiency. Studies—and experience—show that tasks become harder to switch when tasks are less familiar. More complex tasks have different rules and contexts that we need to switch to, which takes more time and attention. It is also important to not multi-task while learning something new because according to studies with students, our brain will not utilize the necessary regions for memory and flexible thinking.

Finally, multi-tasking can also leave an “attention residue”—meaning you are still thinking about the previous task—that results in a depletion of cognitive resources.

Benefits of Multi-tasking

There are numerous studies that actually demonstrate many benefits of multi-tasking. After placing energizing demands on our attention, multi-tasking has a spill-over effect by leading to increased creativity. Although we can make more errors in the short term with multi-tasking, studies show that what actually follows is greater ideation and cognitive flexibility. One incredible study shows that individuals creativity actually increases after they finish multi-tasking. The advantage of this state is that otherwise disparate ideas can be connected in new and original ways; holding contradictory ideas and conflicting perspectives actually creates more cognitive flexibility. In other words, creativity is actually available in multi-tasking—not just in the immersed or diffused style.

Multi-tasking is also activating by nature, overriding procrastination, creating alertness and pro-active behavior. It is this activation that can actually foster cognitive flexibility and creativity.

Multitasking –> Activation –> Cognitive flexibility –> Creativity

Another interesting study shows that “media multitasking”, or switching rapidly from one social media platform to another is correlated with higher levels of creativity as well. Rather than seeing social media as a complete distraction, we can approach these habits as an opportunity to let the mind wander and loosely gather ideas. Social media use should of course be handled carefully as other studies have clearly shown a link between media multitasking and symptoms of social anxiety and depression.

Temptation bundling (see Katy Milkman’s fascinating research) is another way to approach multi-tasking. Simply couple one task that you find boring with another that you find interesting (e.g. open the mail while listening to your favorite music).

Diffused Focus

Diffused Focus is when we don’t focus on anything in particular and let our mind wander a broad range of thoughts and feelings.

Opposite to Immersed Focus, this style is often avoided or neglected because it is seen as unproductive, indulgent or boring. However, Diffused Focus has tremendous value to our work because it allow us to solve problems that we not be able to in more intense focus states. When we allow our mind to scatter, we are accessing and connecting new ideas, taking different perspectives, and finding solutions to problems that we might be otherwise be stuck on. Diffused focus is a restorative state that, similar to flow states, has low stress levels. In his brilliant book Scatterfocus: How to Manage Your Attention in a World of Distraction, Chris Bailey underscores the importance of letting our minds wander intentionally so we can derive the most benefit from this state.

As with other states of focus, some simple steps can be taken in order to tap into benefits of Diffused Focus.

- De-stimulate and simplify your work environment

- Let go of the goals

- Daydream

- Record your thoughts

- Have one routine (e.g. going for a daily walk) in which intentionally allow your mind to wander

- Pick a tough problem to solve

Interestingly, when our mind wanders, some research shows that it goes to 3 main places: past (12% of the time), present (28%), & future (48%). In other words, Diffused Focus is a great opportunity to not only untangle difficult problems at work but start to brainstorm new ideas for the future.

Summary

In short, flexing between different focus styles can improve your leadership and work performance. When leveraged intentionally, each style of focus can allow you to more adaptively solve problems depending on the situational demands.

- Leverage the strengths of all focus styles

- Recognize the limits of each style

- Know how to on-ramp and off-ramp each focus style

- Recognize which focus style you typically overuse and do that less

- Recognize which focus style you neglect and do that more

| Focus Style | When to Use it | When not to use it |

| Immersed | For execution and high levels of performance | For working on new skills, low-value work |

| Sustained | For when you need to complete or problem-solve something complex; For new areas of learning | When you need to attend to needs of the team; juggle commitments; when you can’t limit distractions |

| Selective | For accomplishing a specific, short-term goal; For decision-making in distracting environments | For daydreaming/generating creative ideas; for complex projects |

| Multi-tasking | For familiar “second nature” tasks; for stimulation and generating creative ideas; For scanning and monitoring your environment | For unfamiliar tasks, new skills/areas of learning |

| Diffused | For new perspectives, ideas and solutions; when you are cognitively depleted | For when you need to finish something or perform |

Resources

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342113884_More_tasks_more_ideas_The_positive_spillover_effects_of_multitasking_on_subsequent_creativity